Dogs Managing Crisis

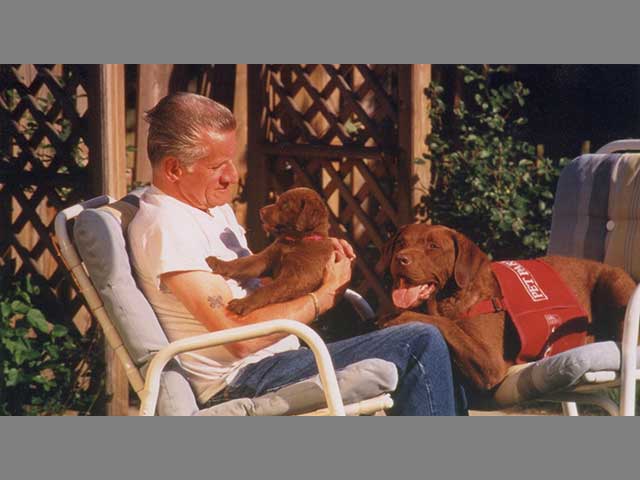

By the time Sophie had a litter of puppies, Silver had sharp instincts for detecting therapeutic potential. She singled out one puppy, Lucy, who was destined not only to become a great therapy dog, but also the number one Chesapeake in America.

One day Silver was introducing Lucy to a group of medical professionals, when a skeptic offered this challenge: "I just don't understand what a therapy dog does." Silver realized that she had never formed a description of pet therapy. "I talked about how we work with occupational therapists and physical therapists," Silver says. But this was not making her case. Then Silver scanned the audience, and found her answer. It was 4:00, near the end of a long day. "I told them, 'Look at all of you. When I walked in here, you were falling asleep. But now you're all lit up, laughing, bright and alert, asking questions.' The person who had asked me the question said, 'you know, you're right.' They saw for themselves how therapy dogs get to people."

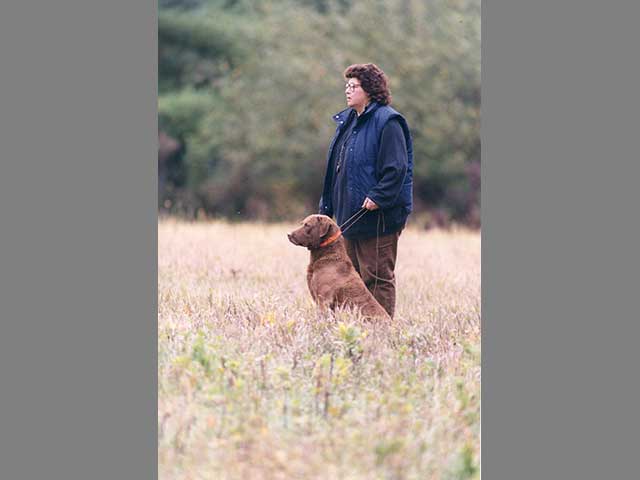

Silver realized that she enjoyed doing therapy, and also explaining it. This inspired her to begin conducting classes where she teaches people and dogs how to become pet therapists. "I show them how a good therapy dog is reliable, outgoing, and wants to be petted without bouncing all over the place. There is also good basic obedience."

This should sound familiar to anyone with success in the show ring. Silver says that show dogs are not just about looking pretty, that with some additional training they have potential to be great therapy dogs. "Show dogs are used to being handled, having their teeth and ears examined, having someone go over every part of their body. They are very well socialized, self-confident, dependable on the end of the leash. All this makes them perfect for going out into the world to work with people."

In her therapy classes, Silver emphasizes that it is not just the dog that must be receptive and calming. "You can't talk down to people, even unintentionally. You need to know how to help people get their minds off stressful situations onto another subject. Just like in the ring, therapy is a partnership. If you're nervous, it goes right down through the leash and your dog detects something is wrong."

Watching her students, Silver is always testing, offering sharp, but honest, evaluations. "I'm analyzing the person and the dog. If someone gets angry because I said they need to improve, they probably won't be good at therapy, even if they have great dogs."

Silver and her dogs settled into a comfortable pattern of hospital work, teaching, and showing. Then, like the rest of the country, she was shocked by the terror attacks of 9/11. Silver knew that she and her dogs could offer their assistance. By September 12, Silver was in a makeshift disaster-relief center at Liberty Park in New York City, along with Lucy, and Lucy's young daughter, Maddie.

They met with desperate and bewildered people. "We worked with children while their parents went into another area to locate family members. Other times, adults came over and we'd go into a private section to talk."

Silver and her team also helped Red Cross workers. "They came in after their shifts to reduce their own anxiety. They were from all over the country, and they talked about leaving their families behind to volunteer in New York."

Although this was related to the therapy work she had been doing for years, 9/11 brought out new skills in Silver and her dogs. "We began calling this 'level-two' therapy work. These dogs had to hold up for several hours straight, and the handlers couldn't fall apart listening to crises. If you acted stressed, the dog could pick up on it. That would stress the victims more."

In those confusing days, as she and her Chesapeakes officially added "disaster relief" to their achievements, Silver was already formulating what must come next. "I realized that only a few people and dogs can handle these kinds of situations. Anyone without good preparation wouldn't be able to do it." She helped develop a set of standards and tests to determine which dogs and handlers are suited to disaster relief. Today, in addition to therapy, Silver conducts classes in disaster relief skills.

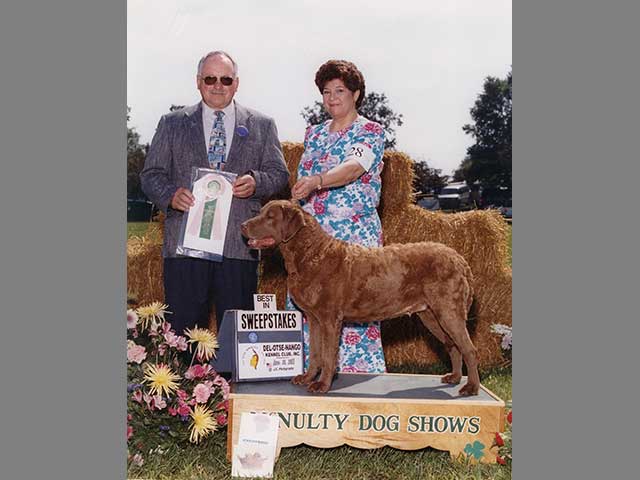

Through all this, Silver kept competing in the ring. Maddie became an AKC champion. Not contented with winning in America, she headed north, where Maddie earned her Canadian championship. Modestly, Silver explains, "We're so close to the border, it's easy to go up for shows."

Silver sees the show ring as an untapped resource. She does not proselytize, but when fanciers show curiosity about therapy work, she is encouraging: "I tell them to get out there and try doing therapy, an hour a month. If you have a retired show dog, this could be perfect. Given the opportunity, and training, show dogs are capable of learning more, and they can go way beyond the ring."

Silver also urges people to consider the next level, disaster relief, where the challenges, and the rewards, are even greater.

When she is showing, Silver does not mention her humanitarian achievements, although she is confident that skilled judges know which dogs have the muscle tone and conditioning for a hard day's work. Just to make sure, Silver began doing presentations to judges about Chesapeake Bay Retrievers. "I tell them that you can have a dog that looks absolutely beautiful. But I show them how to tell which dogs can also work long hours, which dogs have a sound temperament." In this way, Silver says, she shows there is a connection between the qualities needed for success in and out of the ring.

Maddie recently had a litter of puppies. Some of them are headed for greatness in the ring, in disaster situations, and in private moments as therapists. Silver also plans to broaden one of her other endeavors – going into schools to teach kids about dogs as part of the AKC's ambassador program. But that is another story.