Twisted Inside

Williams recalls one of the first times she competed with Red: "After we all went around with our dogs, the judge told me to take him and go over into the corner and wait. I was worried, and didn't know what this was about. We watched all the other dogs go around again. Then the judge asked me to take Red and circle one more time. The judge said to everyone, 'I want all of you to take a good look. This is what a German Shepherd is supposed to move like.' That's the way I remember him."

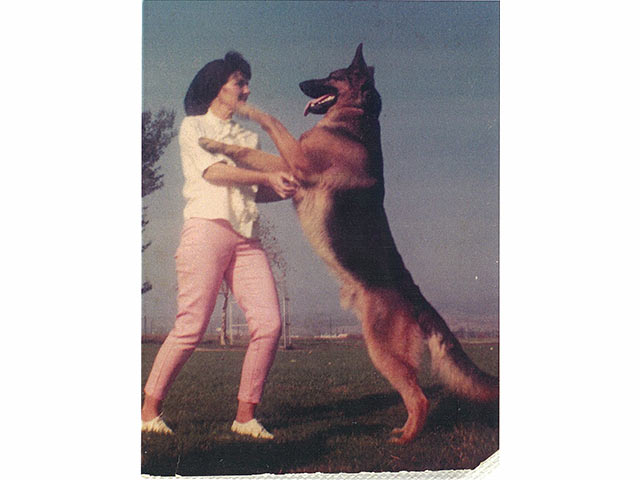

Red became one of the country's top winning Shepherds, and Williams received regular phone calls from people wanting to breed their dogs to him. "He had absolutely beautiful movement," she says, "and outstanding temperament. And all his offspring were the same – just phenomenal." Williams and Red were the center of attention at every show they attended.

Painful Surprises

Late one night, when Red was nine, his abdomen suddenly swelled and he got a stricken look in his eyes that Williams had never seen before. "Once you see that look, you'll never forget it," she reports, her voice trembling even 20 years later. "It's like they know they are going to die. You see dogs get hurt sometimes while they're playing. This is different. They stand in a strange manner, with their heads down. They start retching like they want to vomit, but can't. They try to listen to you and follow your commands, but they just have this hopeless look. They are in sheer pain."

Williams raced down a California freeway to the nearest veterinary hospital, at the University of California, Davis, where she learned that gases had built up rapidly in Red's stomach, making it swell to more than double its regular size.

Veterinarians released the gases by inserting a tube along Red's esophagus into his stomach. He had made it through this ordeal. But Williams learned that it was almost certain Red would have another bloat episode. And he was highly susceptible to torsion, a deadly relative of bloat. With torsion, the stomach not only swells, but twists, literally wringing itself.

Susan Hamil helps manage a veterinary clinic in Laguna Beach California, and breeds American Bloodhounds, which are highly susceptible to bloat and torsion. She has seen her own dogs torse, as well as many others who come into her clinic. "Imagine what kind of pain the dog is going through. It's like the stomach is a full balloon twisting on either end and squeezing the air against its sides with incredible force. It sets off a cascade of other reactions, compromising the heart, spleen, nerves, and sends the dog into shock."

Ms. Williams returned home with Red, but their life together was altered. "I wanted to make sure I was there if this ever happened again. I slept at night with his lead around my shoulder, so if he moved, I'd move. When my husband and I went to the grocery store, one of us sat in the car with Red. If we came out and the car was gone, it meant Red had bloated."

Within two years, Williams again found herself racing down the California freeway. This time, Red had bloated vanaand torsed. She got him to the hospital in time for emergency surgery. "But when they operated on him, he had all these lesions from previous episodes. He died right on the operating table."

For more than 30 years, Sherry Wallis has been breeding Akitas, which also have a high incidence of bloat/torsion (it is the number one cause of death among male Akitas and number two in females). Wallis has seen this condition strike her own dogs, and has learned to notice the warning signs. She describes the same "unproductive vomiting" Ms. Williams mentioned, adding, "They have a glassy-eyed look, a sure sign, because they are in agony. The minute I see that, I get into the car and race to the vet. I don't worry about overreacting."

Ms. Hamil says surgical techniques have vastly improved in recent years, to the point where about 80% of torsioned dogs can be saved. Surgeons try to reset the stomach, then use special tacks to attach the stomach to the chest, which prevents it from twisting again, a procedure known as gastropexy. This reduces the chance of future episodes by about 85%. But Ms. Hamil says there is one catch: "You have an hour or two to get to the hospital and begin surgery."

What About Prevention?

For decades, owners with dogs prone to bloat/torsion followed a set of standard preventive measures. In 1998, Dr. Lawrence Glickman, professor of environmental health at Purdue University School of Veterinary Medicine, began testing this received wisdom. "I was amazed that, while bloat is a significant cause of mortality in many breeds, there had been very little research done to look at causes. It was also clear that we couldn't study the animals in the laboratory. We had to study them in their natural environment." This approach is in line with Dr. Glickman's 30 years of research experience, which he says "includes diet, as well as the rest of the animal's environment."

Dr. Glickman's findings shocked everyone in the dog world. Not only did he reveal new ways to ward off bloat/torsion, he also discovered that some of the standard advice was harmful.

In the initial phase of his study, Glickman and his research assistants measured 1,940 dogs. "I went to about 26 shows in about 20 different states over two years. This was the only way I could evaluate the dogs in a standard and systematic way." He measured body type, assessed temperament, and collected other facts from owners.

He then tracked the dogs for three years, carefully monitoring diet, activities, temperament, and more. "For the first time, we had numbers to actually show what percentage of dogs in various breeds bloated. It was astronomically high for some breeds, where nearly 40% of them bloated at some point."

Glickman discovered a number of useful facts. The most striking ones had to do with food. "We found very consistently that dogs eating only dry food had a higher risk of bloat. It didn't matter whether the owners added canned food or table scraps. As long as it was not dry-food-only, the risk went down."

Glickman wondered why this was true. Armed with veterinary records dating back to 1965, he noticed a pattern. "Prior to about 1984, very few dogs died of bloat. There is a dramatic increase, about 1,200%, from 1984 to 2004." These numbers are so staggering that something had to be going on to account for it. "You think, maybe the diagnostic techniques got better. That might be true for disease like cancer, but with bloat it's a no-brainer – you never needed a sophisticated test to prove it."

What else changed in dog care in the early 1980s? "Two possibilities came to mind – food or vaccines. But vaccines didn't change much, which left food." Glickman called all the large pet-food companies, and found a consistent pattern. "Prior to 1982, dry dog food was baked. Then they went to a new process where they formed kibble made from pellets cooked under high temperature and high pressure."

Glickman got further proof from the military, which had such a serious bloat/torsion problem they consulted Glickman. He found that military dogs are fed an all-dry-food diet, and, just as it was with his study subjects, beginning in 1984 there was a steep rise in the number of torsion-related fatalities.

For comparison, Glickman looked at the German military, where their dogs almost never die of torsion. "They use the same breeds, and the dogs go through the same training. The difference? In Germany, they cook for their dogs."

It is not only what, but how, dogs are fed, that affects the probabilities of bloat/torsion. People had long believed that bloat-prone dogs should be fed from elevated food bowls, and manufacturers began marketing elevated bowls as an effective safeguard. Glickman's study turned this idea upside down. "We found that not only was this untrue, but it actually increased the risk by up to 200%. It's especially important for people to know when something promoted as preventive turns out to be detrimental."

It was a common belief that drinking large volumes of water with meals was dangerous. Glickman found it to have no effect.

Many people believed that adding water to the dry kibble could help prevent bloat. Some food companies claim to have developed better ingredients, such as eggs, or changed the order of the ingredients to make their foods less likely to cause bloat/torsion. It was believed that corn was a culprit. Glickman's study contradicts all of these claims. "We found that it has more to do with the form of the food, not the composition."

Glickman did find that feeding dogs more meals per day helped to reduce the likelihood of bloat. "More, smaller meals means less food going into their stomachs each time."

It was common wisdom that stress, or even general unhappiness, contributed to bloat/torsion. (Many breeders continue to believe this). The findings proved this to be untrue. "We asked people what their dogs did right before they bloated," Glickman explains. "We also measured temperament. Then we found people with dogs of the same breed, age, and temperament, but had never bloated, and asked them the same questions. The list was exactly the same."

Ending the Pain While Waiting for a Cure

Connie Vanacore has decades of experience breeding Irish Setters, which are often stricken with bloat/torsion. She has been part of numerous health initiatives at the Irish Setter Club of America, including Dr. Glickman's study. As she explains, "The study had many surprises for us all. When his research came out, we put his findings into articles in our newsletters and sent out information to our members so they could pass it on to puppy buyers and tell people what to look for." All other national breed clubs for high-risk dogs did the same thing.

Although many of Dr. Glickman's findings could be easily implemented, some were a challenge. One central discovery was that breeds with deeper, narrower chests appear more likely to have bloat/torsion. "To follow the results," Vanacore says, "you'd only breed dogs with wider chests. But we aren't going to do that. Our breed standard calls for narrow chests, which also gives the dogs greater lung power." Adding strength to Glickman's findings, Vanacore says there is a separate line of Irish Setters, with broader chests, which are far less likely to bloat.

According to a key rule of breeding, eliminating a favored body type just to avoid bloat would not only alter desirable physique, it would be detrimental to overall health. What is needed, Vanacore and other breeders say, is a way to know which dogs are genetically predisposed to bloat/torsion. That would allow breeders to keep dogs with the preferred body type, but know which ones are more likely to pass bloat/torsion to their offspring. "For now," Vanacore explains, "we have management, not breeding practices."

Uncovering the genetics might also help breeders deal with one of the most complicated aspects of bloat/torsion: it usually occurs long after the dog has already bred. When older dogs bloat, it complicates breeding choices. Was it genetic, and should the breeder cease breeding to that line, or was it simply related to aging? "If I see Akitas bloat at just nine months old," Ms. Wallis says, "that's a major red flag. I won't breed from that line. But if an older dog bloats, you might go back and see some history of it, or you might not see any other dogs that had it. Age is a tricky thing."

One day soon, genetic tests may solve this dilemma. In the meantime, Ms. Williams urges her fellow breeders to make full use of pedigrees to stop breeding clearly affected lines. "If you really love your dogs, there's nothing worth putting them through such excruciating pain. Why would you do this? To even consider breeding dogs you know are affected is inexcusably cruel. My biggest hope is that bloat/torsion can become a rare thing. But for that to happen, everyone has to be involved."

Future Possibilities

Along with offering practical advice, Dr. Glickman's study also opened new questions to pursue. He would like to do a study that compares the physical characteristics of dogs within each breed that bloat with those that do not, to determine what the differences are. Specifically, he says, there is a mine of possibility in the anatomy of the esophagus and the stomach. "A large European study looked at motility of the esophagus. Three-quarters of the dogs that bloated had irregular swallowing activity, which caused them to gulp a lot of air."

The European findings seem to dovetail with another of Dr. Glickman's discoveries. Although food composition in general was not a factor, when fat is listed among the top three ingredients, there is a higher chance of bloat. "This has to do with the motility of the stomach. Fat slows the stomach down." He says that canine bloat shares something with a rare human form of bloat. People with this condition also have an abnormally functioning esophagus.

Unlike cancer or hip dysplasia, Glickman says, bloat/torsion is easy to see and easy to report. "There are virtually no researchers involved in this," Glickman explains. "Yet it accounts for as many, or more, deaths in certain breeds than any other cause. If I were going to put my money into a genetic study, I'd do this instead of cancer or hip dysplasia, which are much more complex. This doesn't require sophisticated equipment to diagnose. The owners can tell you if the dog has it! If we put the money into it, we could go a long way."