Clearing the Lines: Wisdom of Genetic Testing

"People were afraid to find out what they didn't want to know," he explains. "But isn't it worse to keep having puppies with problems? I was accustomed to my dogs living 12 or 14 years. But all of a sudden, they weren't reaching eight or nine. My dogs were being taken away from me earlier than they should be." He carried photos to dog shows. "I would tell everyone, look at this dog. He's beautiful. But I can't breed him, because he has this disease." Newman told people they had to face this problem and find the cause.

That was in the mid-1990s, when Newman's approach was unconventional. Today, a terrible disease in Mastiffs is being wiped out, and anyone in the Mastiff Club of America who is silent about it is criticized — a complete reversal. All without losing the wonderful traits Dr. Newman loves to brag about in his dogs.

The Power of Genetic Knowledge

Throughout history, humans have bred dogs just by looking at physical characteristics, or phenotype. This is a game of chance, but it is still generally the only option breeders have. Three or four generations can pass without a problem. But one day, half the puppies in a litter are born with a health problem. This is mysterious, since both parents appear to be healthy. The cause lurks many levels beneath the surface.

Every tissue cell in the body of a dog (or human, or any other animal) has a nucleus. Zooming in on the nucleus, 78 finger-shaped chromosomes float into view. Chromosomes are like wrappers, and peeling away the surface reveals what looks like a necklace made of thousands of tiny beads. This string of beads is DNA, a molecule that can replicate itself, the basis of almost all earthly life. Each DNA necklace is a double strand, and the whole structure twists in a spiral. Along this double strand, certain clusters of beads work together in an invisible bond. Those clusters are genes. Nearly every imaginable trait derives from one or more genes.

Healthy genes have a pattern. When a dog is diseased, scientists know that somewhere at least one gene has a mistake — the sequence of DNA beads is wrong, or one or more of the beads is damaged or missing. The challenge is locating the mistake. Every dog chromosome has 50,000 to 100,000 genes, and this is repeated throughout the chromosomes. Even with modern computers, analyzing all canine genes is laborious. Also, the genetic makeup of most dog breeds, as well as their diseases, vary considerably, requiring a unique study for each disease in every breed. To find the cause of a disease, researchers must move methodically through all the DNA, looking for a gene with one pattern in healthy dogs and another pattern in diseased dogs. If this can be achieved, screening of hundreds of blood or skin samples must then be done, to establish beyond doubt the disease gene's location and appearance. At that point, any genetics laboratory can collect a cheek swab from a dog, zoom in on the specified gene, and say for sure whether the dog is affected (suffers from the disease), a carrier (has the disease gene but is unaffected), or clear (has no sign of disease). It can also be determined whether the disease came from the father or the mother. This is a genetic test.

With a genetic test, it would no longer be a mystery how those diseased puppies were born from two apparently healthy parents. The breeder would know that the parents were both carriers for a disease, a combination that all but guarantees problems.

Talking About a Problem

Although most breeders have had some puppies born with a breed-specific disease, they are often reluctant to mention it. Their dogs might be branded as "defective," spelling the end of their kennel's reputation. Every pet owner can sympathize with another source of breeder reluctance: the desire to shield ourselves from the idea that a loved animal may become blind, or die of heart disease or cancer.

But while people remain silent, a disease builds momentum. Dr. Mary K. Boudreaux, a researcher at Auburn University who studies genetic blood disorders in Great Pyrenees and Otterhounds, says, "People go along, and half their litter are carriers. But because there are no clinical signs, they have no idea it's happening. Until one day they breed a carrier to a carrier. The sad thing is, people assume they have a problem under control." She says that breeders are often surprised to hear what percentage of a breed can silently become carriers. "The carrier population gets to about 30% before people realize there's a problem. By that time, it's one of the most difficult and disheartening things to deal with. And the sad thing is, it could be avoided."

A few years ago, Dr. Bill Truesdale, president of the American Boxer Club, began seeing a sudden increase in the prevalence of cardiomyopathy, a heart disease. Research showed that 25% of all Boxers were carriers for cardiomyopathy. Truesdale was one of the people who decided that the silence had to be broken. "We were all hiding this dirty little secret about the illness," he said. Boxer owners felt so helpless, they lowered their expectations of how long their dogs could live. "It was sad. We all just became used to having our dogs die at nine years old. Eventually you have to fess up and figure out how to breed the least-affected dogs."

Truesdale's message to his fellow breeders in the American Boxer Club was designed to end the denial, without singling anyone out. "Suddenly, four of the top ten stud dogs died of cardiomyopathy at a young age. A lot of us got together and finally confessed that we had all seen it in our lines. So it's not about condemning anybody. It's about getting everyone to be part of it." When a devastating form of bone cancer spread among Mastiffs, Dr. Newman chose a similar tack. "I said, 'Look, we're all breeding in a small gene pool, and when you breed over and over again you're bound to have some combinations come out that you don't want.' I was positive. I just said, 'Let's all just look at this problem together.'" With leadership, people came forward. "It became like those groups of parents who have all lost a child to some disease," Newman says. "You have a common interest. You join together to help each other. Now we have a Mastiff Club support group that helps anyone with a health problem."

When a Breed Club is Ready to Act

After admitting they have a health issue, a breed club wants a researcher on the case as soon as possible. But most dog breeders are not geneticists, so it would be overwhelming for them to judge specific research proposals. This is where the Canine Health Foundation (CHF) comes in. Formed in 1995, the CHF is a non-profit organization that communicates both with breeders and researchers. It collects donations from individual breed clubs, and combines the funds for more leverage. They then direct funding into the most promising research projects. Erika Werne is the director of canine research and education at the CHF. "After our first five years, we were working with about 40 breed clubs. Now we're working with 100." This growth is due to the expansion of research over the past decade, as well as the trust breed clubs have in the CHF.

With a staff of trained scientists, Ms. Werne explains, "The CHF speaks to clubs and helps them identify problems. And we have contacts in the research world, more than individuals in a club could have. We find the best researcher for the job, we go out there and solicit projects, and we work with investigators who would be interesting to clubs."

Ms. Werne says that the CHF exists to serve breed clubs. "We do our homework and make sure that projects we fund are ones the breed clubs would support. We always want to be able to say that we are spending their money as wisely as possible." Research grants from the CHF range from $75,000 to $100,000 for two years, a significant sum. The CHF reports on a regular basis to donating clubs about how funds are being spent and how the research projects are advancing.

Dr. Newman says he and his friends in the Mastiff Club are glad to have the CHF around. "Researchers are kind of like kids in college. They write home and say, 'Dear mom and dad, everything's fine. Please send more money.' The CHF can review the grants, do the critiques and evaluations about what's going on. We don't know how to judge if a researcher is giving us good information. That's why we work with the CHF."

Most of the time, researchers need blood samples, along with pedigree information about dogs. But sometimes the just need simple facts. Liz Hansen, a researcher at the University of Missouri, is developing genetic tests for various forms of canine epilepsy. "We have a seizure survey that collects clinical data on 83 different breeds, including information about each dog's seizure, what testing has been done on the dog, medications the dog is taking, and the reactions to those medications." This information helps Hansen and her colleagues tease out vital patterns.

Hansen, along with other researchers, emphasizes that blood samples and data are needed for all dogs in a breed being studied, whether or not the dog has the disease. "It's difficult to motivate people to provide information on healthy dogs," she says. "But that is just as important. Otherwise, we can't compare what's normal and what's not."

All data collected by genetic researchers is protected. Dr. Elaine Ostrander, chief of the cancer genetics branch of the National Human Genome Research Institute, and an expert on canine genetics, describes a strict ethical code. "Anything you tell us about your dog's health status is kept confidential. The fact that you chose to participate in research is not revealed to the AKC, the CHF, nor to other members of your breed club. Anything we find in the course of looking at your dog's DNA is not disclosed to anyone, not even to you."

Towards a Perfect Test

With the breed clubs watching, the pressure is on researchers to achieve the ultimate prize of a genetic test. But researchers beg for patience. A genetic test may be ready in under five years, but it may take several years to obtain enough DNA samples, or to find a genetic pattern. Diseases like hip dysplasia and epilepsy are caused by two or more genes (polygenic), multiplying the time and effort at every step. Many forms of cancer are not only polygenic, but are also caused by a combination of genes and environment.

The good news is, researchers make worthwhile discoveries along the path to a genetic test. There is something called a marker test, a type of genetic test that is not 100% reliable because the exact gene is not found, but which still allows breeders to increase the odds for healthy puppies. The American Boxer Club has used a marker test for cardiomyopathy. According to Dr. Truesdale, this has already extended the life span of their dogs. "We're more often seeing Boxers live to 13 and 14 years old now. So we're going in the right direction." He and his breed-club members are looking forward to the benefits of a true genetic test in the near future.

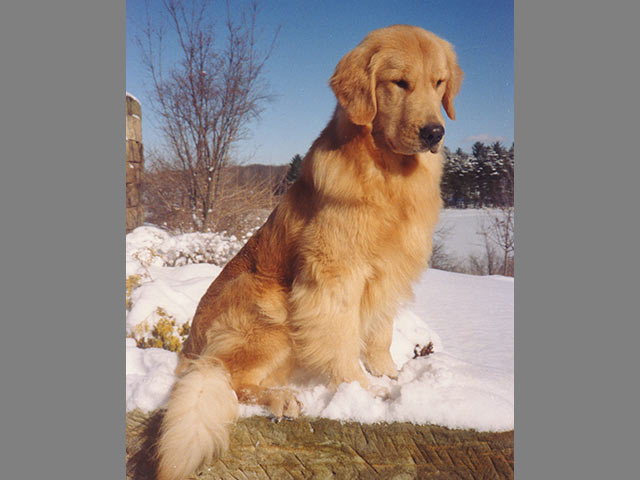

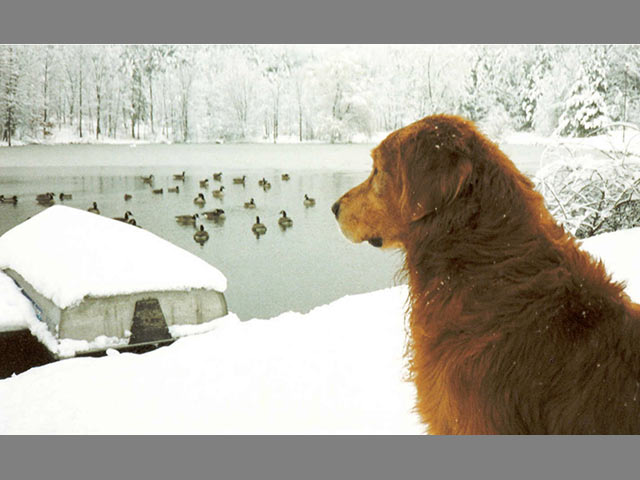

Even before a genetic test or a marker test, researchers offer other important insights. Rhonda Hovan, a member of the Golden Retriever Club of America, says, "We don't expect to have a simple DNA test for cancer in Goldens. But we hope to understand which dogs are at higher risk. That would help us make more informed breeding decisions."

Ms. Hansen says that even though epilepsy is one of the most complex of all diseases, her laboratory recently discovered a marker for a form of epilepsy that plagues Standard Poodles, and they are closing in on the culprit gene. "We're down to just 300 candidate genes." Even better, the discovery was made the day before the Poodle national dog show. "That was really timely. We told them that we might be in just the right spot, and we have more testing to do. But it was very exciting, to go in front of that group and tell them we're close. Those are the same people we've been working with. They are the ones who have provided all the blood samples and information we needed."

Using Genetic Tests Wisely

Dr. Boudreaux has achieved the highest form of success, a reliable genetic test for a platelet disease affecting Great Pyrenees and Otterhounds. Similarly, Dr. Jeanette Felix, president of Optigen, a commercial genetic-testing agency, was proud to share excellent news with Irish Setter owners in June of 2005. "We have a significant new test for a blinding disease. And the same mutation appears in 12 other breeds." With a simple cheek swab, a breeder can know within a few days if their dog is a carrier or clear of disease.

The question then becomes, how should breeders use the information? The first reaction might be to stop breeding any dogs who test even as carriers. But this is unwise. Removing carriers from breeding eliminates disease genes, but it also removes several positive traits. Because all purebred breeding starts from a limited gene pool, selecting out all carriers creates new health problems that may be as bad as the original disease, especially if the carrier population has reached 25% or 30%.

John Duffendack, president of VetGen, a commercial provider of genetic tests, offer a straightforward solution. "Even if a dog is a carrier, you can still breed that dog to a clear. The clear will always contribute good genes. The carrier half the time contributes a good gene and half the time contributes a bad gene. The pups will be half clear and half carriers, but none will be affected. Do that for a generation or two. Don't breed carriers to carriers, maintain the characteristics you want, and you breed out the disease."

The Future of Genetic Testing

For those breed clubs that have fully embraced genetic testing, silence about disease has been replaced by enthusiasm. Researchers all agree that the science warrants even greater enthusiasm, that in the foreseeable future many debilitating diseases can be eliminated from purebred dogs.

It is an exciting prospect, but there is a lot of work to do. Mr. Duffendack sums it up: "There are somewhere around 600 to 800 genetic diseases in dogs. We know about less than 50. There is a great world of undiscovered genetic tests, some of which are very important, though very difficult. Given enough time and resources, we will certainly find the answers."