Icy, Passionate Pioneer

Born in 1891 in Worcester, Massachusetts, Eva Seeley grew up in an era filled with influential people and events. Although Seeley lived in Massachusetts at this time, her imagination would have been drawn north, to Alaska, where each winter amazing stories were told about dogs and sledders. From October through May, when all the rivers were frozen and the air swirled with dangerous ice storms, traveling by boat and plane in Alaska was not possible. Dogsleds were the answer, and during Seeley's youth they had become a common sight. From a young age, Seeley also loved sports. In 1908, then Eva Brunell, she enrolled at Sargent College, in Boston, as a physical education major. It was at Sargent that Seeley, under five feet tall, acquired her life-long nickname, "Short." Seeley was far ahead of her time, living in an age when it was uncommon for women even to attend college. It was even more unusual for a woman to study physical education.

The same year Seeley entered Sargent College, the All Alaska Sweepstakes began, a 408-mile recreational race between Nome and Candle. As the New York Times reported in April 1909, "hundreds of thousands of dollars were wagered" in bets on which dog team would be victorious. For having the fastest time, the winner took home "a purse of $11,000 in gold and will hold for a year the handsome Suter Trophy," The New York Times reported.

Seeley graduated from Sargent in 1912 and taught physical education in Massachusetts schools over the next 10 years. She would have heard all about the Alaska Gold Rush, which was in full swing at that time. Dogsledders trekked into forbidding regions, often hauling out as much as a ton or more of gold using teams of Siberian Huskies and Alaskan Malamutes. Arthur Walden, a racer and breeder of a dog called Chinooks, was one of the first adventurers to head into Circle City, Alaska, to seek fortune. In his book, A Dog Puncher on the Yukon, Walden describes how forbidding Alaska was at that time: "Here was a town of some three or four hundred inhabitants which had no taxes, court house, or jail; no post office, church, schools, hotels or dog pound; no rules, regulations, or written law; no sheriff, dentist, doctor." Heading out into frozen lands to locate gold, Walden writes, sledders did not even have thermometers, except for one which he describes as "a set of vials, one containing quicksilver, one the best whiskey in the country, one kerosene, and one Perry Davis's Pain Killer." Walden humorously writes that a traveler could determine the severity of the temperature by seeing which of these liquids had frozen and became unusable. In this inhospitable region, Walden and others relied on their dogs for survival.

In 1924, Eva and her new husband, Milton, went to New Hampshire for their honeymoon. They fell in love with this region and moved to Wonalancet. A short time later, Eva and Milton visited Arthur Walden's Wonalancet Kennel. The Seeleys adopted one of Walden's Chinook puppies as a pet.

A year after Milton and Eva moved to New Hampshire, the most riveting story in sled dog history was about to be told. In January 1925, Seeley, along with hundreds of thousands of others, tuned in to radio reports of the Great Serum Run, a race that made dogsledders, and their dogs, into saviors. In Nome, Alaska, the native population was on the brink of a diphtheria outbreak that was sure to decimate their community. Weather conditions made it impossible to use planes or boats to transport the serum to Nome. Quickly, a relay circuit of 20 dogsledders and 200 dogs was organized, each covering a section of the journey. Like others around the world, Seeley would have been awed by the sheer impossibility of this feat: dog teams had to sled almost 700 miles in temperatures plunging as low as -62° F, fighting through frigid, blizzard-strength winds and three-foot-high snow drifts. Two of the most acclaimed characters from the Great Serum Run were Leonhard Seppala, and Togo, his 12-year-old Siberian Husky. With Togo as lead dog, Seppala raced his sled team over a particularly treacherous 340-mile stretch of icy terrain.

On February 2, in the semi-darkness of the Alaskan winter, Gunnar Kaasen and his dog Balto slid into Nome, delivering 300,000 units of serum to halt the diphtheria epidemic. Interviewed for a February 3, 1925, New York Times article, Kaasen described how a blizzard made it impossible for him to see either the trail or his dogs. "A gale was blowing from the northwest. I gave Balto, my lead dog, his head and trusted him. He never once faltered. Balto knew the way we were going." The circuit of racers and dogs completed their historic run in just five days. Normally, this distance took three weeks for sleds carrying mail or supplies into Alaskan mining towns. On February 6, 1925, Senator Clarence Dill of Washington State led the United States Senate in entering the extraordinary facts of the Serum Run into the Congressional record. In his speech, Dill contrasted the Serum run with all previous races, stating, "Men had thought that the limit of speed and endurance had been reached, but a race for sport and money proved to have far less stimulus than this contest in which humanity was the urge and life was the prize."

In 1929, Arthur Walden, like Leonhard Seppala, had a shot at high-profile adventure, although it was on the other side of the globe. Walden accompanied Admiral Byrd to Antarctica, taking his original Chinook dog with him. For the two years he was away, Walden left Eva and Milton Seeley in charge of Wonalancet Kennel. Meanwhile, not far away, Leonhard Seppala was showing success breeding his Siberian Huskies with dogs hailing directly from Siberia, a program that eventually gained AKC acceptance in 1930.

When Walden returned from Antarctica in 1931, he sold Wonalancet Kennel to the Seeleys. The Seeleys renamed the kennel, calling it Chinook. Eva Seeley had an idea right from the start about what she wanted her dogs to look like, and she was determined to make it happen. Her first step was to cease breeding Chinooks, even though she now controlled the kennel made famous by these dogs. Instead, she obtained a dog from Leonhard Seppala, a Siberian Husky named Toto, daughter of Togo, Seppala's famous lead dog from the Great Serum Run. Toto helped form the foundation of Seeley's Siberian Husky line. In the early 1930s, Seeley traveled several times to Alaska to view the purest Alaskan Malamutes. She brought some of these dogs back to New Hampshire and bred them at Chinook Kennel, establishing the Kotzebue, one of three dominant Alaskan Malamute lines seen in the breed to this day. In 1935, Seeley's efforts were rewarded when the AKC officially recognized the Alaskan Malamute.

In the early 1930s, Alaskan dog sledding was in decline, but it was on the rise in New England. Eva Seeley was the heart of this growing sport. While continuing to breed Siberian Huskies and Alaskan Malamutes at Chinook Kennel, Seeley also began working with Leonhard Seppala to form a set of racing rules for The New England Sled Dog Club, based on those once used in Alaska. Seeley organized races between serious dogsledders, raced her dogs to raise money for charities in the Boston area, and she brought her dogs to public gatherings, carnivals, sports competitions, and other events throughout the Northeast. On December 28, 1933, Eva Seeley and her dogs showed that sledding was more than just sport. In the deep woods of Mount Chocorua, a remote region of New Hampshire, Mrs. Milton Ames was about to give birth. A snow storm had blocked all access roads, and Mrs. Milton's nurse had no way to reach her. Eva Seeley and a team of 11 dogs quickly came to the rescue. Seeley transported the nurse, Beatrice Coots, through the snow to check in on Mrs. Ames. Interviewed for the Boston Traveler newspaper, Coots said, "The woman was nervous up there alone with no one to aid or counsel her." But seeing the dogs arrive instilled confidence. "She is satisfied now that everything is going to be all right," Coots said. As promised, Seeley returned with the nurse a few days later to deliver the baby.

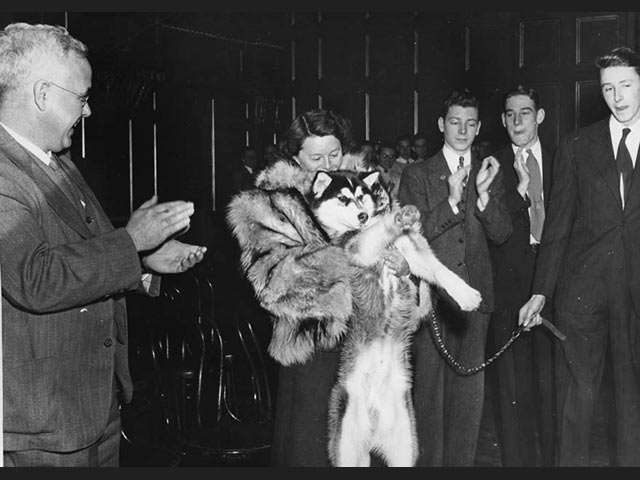

Beginning in 1941, Seeley found a new way to combine her love of sports and dogs, and also to further her mission of bringing the image of Siberian Huskies into the popular realm. That year, students at Northeastern University were looking for an attractive, friendly animal to represent them at their sports matches. There was no doubt who they would contact. Seeley and the Northeastern University administration struck an agreement, and Chinook Kennel provided Queen Husky I as the school's mascot. She was a huge hit. At Northeastern's games, Queen Husky I brought rousing cheers by the student body. Eva Seeley herself was photographed numerous times at these events, smiling broadly as she holds her Siberian Husky for the cameras. After Queen Husky I retired, Seeley maintained a relationship with Northeastern that included seven more mascots. The relationship ended 20 years later, when the university decided to end its program of using live mascots in 1961.

While Seeley was associated with Northeastern University, she began working with the United States military to provide dogs for search-and-rescue missions. During World War II, she ran a school for US soldiers who were getting ready for overseas duty, teaching them how to work as a team with her dogs. Most notably, Seeley provided dogs during the Battle of the Bulge in the winter of 1944-45. By this time, Seeley was a widow, losing Milton to diabetes in 1944. Seeley thrust herself with even greater force into her efforts at Chinook Kennel, continuing her breeding programs for Siberian Huskies and Alaskan Malamutes. Her success was starting to gain the attention of a growing number of breeders around the country who began going to Wonalancet to meet with Seeley.

Seeley provided Admiral Richard E. Byrd with several dogs to serve as part of the 1955-1956 expedition team during "Operation Deep Freeze," whose goal was to build a United States outpost near the South Pole. Unfortunately, at the end of the mission, Byrd's expedition ran into trouble and they were not able to bring the dogs home. Instead, Byrd made the decision to destroy an entire group of Seeley's dogs. Seeley was devastated. Losing these dogs was a setback for her entire Alaskan Malamute effort—Byrd had taken with him crucial members of the breed stock. Negative feelings about the way dogs were treated by the US military was shown in 1958, when a group of young girls petitioned the Navy to buy four Siberian Huskies that were being auctioned off as "surplus government property." The girls were led in their efforts by Eva Seeley.

Starting in the early 1960s, Seeley opened Chinook Kennel to children and adults, introducing Siberian Huskies and Alaskan Malamutes to a wider audience. At public gatherings throughout New England, Seeley organized one- and two-dog sled teams for children, to demonstrate the thrill of dog sled racing. During this period, Seeley's reputation among breeders and judges was spreading rapidly, especially in the Northeast where she took on an almost mythical image. By the late 1960s, anyone breeding Siberian Huskies or Alaskan Malamutes not only knew about "Short" Seeley, but also consulted with her whenever possible. Jean Fournier, a judge, says that her meetings with Seeley inspired a lifelong interest in Siberian Huskies. "The reason I'm a judge today," Fournier explains, "is because Seeley said I have a good eye for these dogs." Wendy Willhauck, a breeder of Alaskan Malamutes, says that those gatherings with Seeley were like watching supplicants seek wisdom from a sage. "It was almost like a cult," Willhauck says, laughing, trying to describe the atmosphere of these meetings. "There was just something magical about the whole thing."

Soon, the meetings became more formalized. Groups of breeders and judges wanted to hear their heroine speak. Jean Fournier says, "We would all sit around and just listen to her." Wendy Willhauck describes how Seeley would also ask breeders to get up in front of their peers and comment on the traits of a specific dog. "We all wanted to see what Seeley wanted us to see," Willhauck says. If the breeders did not name the trait Seeley saw, they could be embarrassed when Seeley pointed it out for them. But if they named flaws in the dog, it could create bad feelings with a friend. "I was in my 20s," Willhauck explains, "and I was mortified. But those are the same methods we use now in judging."

Seeley also expressed her disapproval to any show judge who allowed what she considered a faulty Siberian Husky or Alaskan Malamute to win in the ring. Vincent Buoniello, who knew Seeley for many years, tells the story of how he came to Chinook Kennel after he had judged Siberian Huskies at a dog show. Seeley immediately demanded that he explain why he chose a certain dog to win. After he gave his reasons, Seeley let him off the hook. Other judges did not always get away as easily. Seeley's comments and challenges came from her iron-clad belief in the need to maintain the look and character she had developed in the Siberian Husky and Alaskan Malamute. Seeley knew that breeders and judges were the ones who had the greatest potential to affect her ideals for these dogs, and so she was most demanding of them.

More than just an entourage, this following of breeders and judges helped Seeley maintain her famous Chinook Kennel. Each year, this group gathered faithfully in Wonalancet to work on the grounds and the buildings. But throughout the late 1970s, this effort was becoming more difficult. The money required to keep the kennel running was too great, and Seeley, whose primary love was dogs and not business, was unprepared to deal with the monetary problems. Around this time, Seeley also became a show ring judge. It was an honor, and a nerve-racking challenge, to bring a Siberian Husky or Alaskan Malamute into a ring judged by this iconic figure. While she continued to be a striking influence on the breed, both at dog shows and in her meetings with breeders and judges, Seeley finally had to give up control of Chinook Kennel. Soon after, the facility fell into total disrepair. According to people who knew Seeley, this was a tragedy she never recovered from.

In the early 1980's, perhaps because of the loss of the kennel, Seeley's personality seemed to become more challenging. Those who knew her continued to spread the word about Seeley's vital role in the Siberian Husky and Alaskan Malamute world, and explained that what many saw as negative personality traits were expressions of how deeply she cared about the health and future of her favorite breeds.

Eva Seeley came of age in a day when Siberian Huskies and Alaskan Malamutes existed in relative obscurity, and she was one of the few who believed that these dogs could excel not only at sledding matches but also at dog shows and in people's homes. Through absolute love and tireless dedication, Seeley saw Siberian Huskies and Alaskan Malamutes become recognized and loved throughout the country. Attending any dog show today, you can see living proof of Seeley's accomplishments.