Into the Wilderness

Difficult Question

My next memory: mother, father, little brother, and I in the family van, driving up and down the streets of our neighborhood searching for the runaways. It was dark outside by the time we recovered everyone. I can still picture the last Siberian up ahead as the headlights illuminated her raised tail, her body arching forward powerfully.

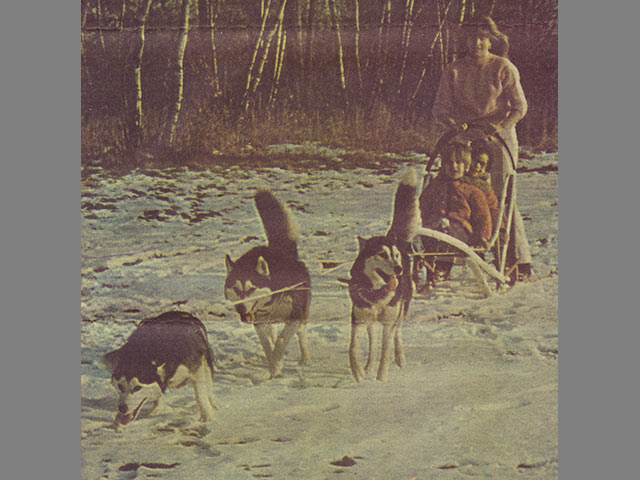

Not long after this, my parents joined The Northern Breed Club, which held events for people with Siberian Huskies, Alaskan Malamutes, Samoyeds, and other breeds. At one event, I got into a dog sled. My mother drove, and three of our Siberians pulled us through the snow. At other events, I stood by myself on the runners. We never went very fast, but there was the same thrill as that night in the backyard. Except now it was under control.

Around this time, my mother brought one of our Siberians, and a dog sled, into my second-grade classroom. It made me proud when she called me to the front of the class to show the other kids how we connect the dogs to harnesses, stand on the runners, step on the brakes, and praise the team.

Then my teacher turned to me. "Matthew, can you tell us what it feels like when the dogs are pulling the sled?" she asked.

I have not been on a dog sled for many years, but I remember the bursting sensation of the dogs' muscles telegraphing along the line, right through the structure of the sled and into my hands and feet.

What does it feel like when dogs are pulling the sled?

Pure Sensations

Karen Ramstead has mushed extensively in Alberta, Canada, her home town. She has traveled to Alaska to compete in the best-known dog race, the 1,150-mile Iditarod, where she spends up to 20 mid-winter days with her dogs, sledding through ice and snow, over rivers and along mountainsides, with temperatures dropping to -30 degrees F and high winds creating snow drifts that camouflage the trail. Still, she admits, "It's very difficult to describe what it feels like!" But then, calling up her many adventures, she offers this: "It's as if the sled is alive with the spirit of the dogs. When the dogs are all motoring along the trail, it's like they are speaking to you through the gang line."

Ramstead has finished three Iditarods, but explains, "If you ask mushers about their greatest experiences, they won't say 'crossing the finish line.' They'll say it's the moonlight on the run, having a great wildlife experience with your dogs. That's what we carry with us."

For Ramstead, non-competitive sledding is as meaningful as the Iditarod. She describes this as a perfect sport for people who want well-trained dogs, and yet want their dogs to maintain a degree of independence. "If I insist on something, I expect it to be followed. However, I also take the dogs' input into consideration, and I let them express their opinions. You don't want to stifle their creativity."

Honed during non-competitive sledding, this creativity often surfaces in more serious situations. Ramstead describes a harrowing example from the 2006 Iditarod: "The wind was blowing harder than I've ever experienced before. We came to a spot where there was no trace of the trail, just this windblown landscape. I couldn't even fathom where the trail was. But I was totally in awe when my dog Snickers found the trail again." Snickers saved the team because she had long been encouraged to trust her own ideas about how to act under any conditions.

Ramstead says sledding offers humans entry into the natural world. "You could go storming into the woods on a snowmobile," she says. "But with a dog team, you're quiet, you're part of it all. You're slipping into the wilderness with them. You get to see a little piece of what they really are. You enter a world where they are the ones completely at home, and they have this knowledge built into their souls. They are just taking you along. But because you're on this shared venture, everything you already have with your dogs goes to a deeper level and strengthens your bond." She promises that anyone who engages in sledding will feel this at some level.

On the trail, Ramstead has seen owls, bald eagles, moose, and more. But most memorable are wolf encounters. "The dogs are definitely more curious about wolves, and the wolves are curious about dogs. It's very different from how they react to moose or squirrels."

One caution: sledding can be addictive. Just ask Donna and Doug Finner. Originally from Florida, they were vacationing in Alaska in 1999 when they saw a sled-dog demonstration. The Finners went for a short sled ride, and at the end, Ms. Finner says, "They put the puppies in your arms." She laughs. No need to explain what happens next.

Describing what it feels like for her to be pulled by a team of dogs, Ms. Finner says, "It's very quiet, very peaceful. You hear the dogs' paws. You hear the runners sliding over the snow." Taking a few moments to consider some sledding scenes, Finner settles on her appreciation of the dogs. "When I'm sledding, I just love to stand back and watch them. They move so beautifully!"

Ms. Finner is a special-education teacher . Before leaving Alaska, she asked about educational materials, and received great ideas to bring back home. "When we're talking about dogs and the Iditarod, my students never miss a class and they never disrupt," she explains. "It amazes me how well the kids connect and respond."

While Donna Finner integrated lessons about dogs into her teaching, she and Doug began searching for their first Siberian Husky. It did not take long for them to go from one to two, then purchase their first sled. After getting a sled, Donna jokes, "I thought, 'you know, sleds go much faster with four dogs.'" And so there were four. Not too long after came the fifth, then the sixth. Why not one more? Their seventh (and supposedly the last) dog arrived in mid-November. The Finners also recently acquired a new sled, and they now live in New Hampshire.

In just five years, the Finners have learned a lot about training their dogs, but they have no intention of becoming Iditarod racers. Ms. Finner says, "We go for six-mile runs now. My goal is to get to 12 to 15 miles. But I know I can be extremely competitive, and that can take some of the fun out of it. I want to make sure that doesn't happen."

The Finners also want their dogs to remain pets, comfortable in and out of the wilderness. "They spend a few hours in the house," Ms. Finner says. "Some of them even sleep in the bed with us."

Taking his turn to describe the experience of sledding, Doug Finner says, "It's truly amazing when everything comes together. You yell 'haw,' the command to turn left, and they go left. You realize it's no accident! They did it on purpose." He says that there is a human-dog connection in all forms of training, but it goes deeper with sledding. "It's like walking into a room with 10 dogs and saying, 'sit,' and all 10 dogs sit at once. That's what it feels like with a dog team, except those dogs are all connected to each other and they're running."

Diane Johnson is the education director for the Iditarod. She helps teachers like Donna Finner develop sledding-related lessons. She is also an amateur musher, with a team of Alaskan Huskies. Familiar with the addictive nature of sledding, Johnson says, "There is something called Iditarod fever. People who go see a race, read a book about it, or just hear about it, all want to learn more." Everyone who loves to engage with their dogs is susceptible to Iditarod fever, whether you compete in 300-mile races or experiment with half-mile stints.

Johnson, like so many other mushers, says, "I'm not interested in racing. I'm in it for the quiet, peaceful experiences." Trying to describe that mysterious sensation of being on a dog sled, Johnson drifts into a particular night-time run near her home in South Dakota. "It was the end of winter. Just me and the dogs out on the trail. There were moments when I would look up and see the moon shining." Sledding through the dark really builds trust in your dogs, since you cannot see everything up ahead. "I was in charge and I knew some things they didn't know," she continues. "But there were things they knew that I was not aware of. There's balance." Her voice rises and she adds, "It's on the border of fright and ecstasy. There's this power, but it's an unknown power. You're in control of your team, but they're in control of you."

Between Karen Ramstead, who races in Iditarods, and the Finners and Diane Johnson, who do shorter events, there are people like Kim and Kelly Berg. They run mid-distance races of about 30 miles. But it all started with one dog.

"When we were 13 years old," Kelly Berg says, "we volunteered at the Humane Society. We got a Siberian/Shepherd cross as our first dog. Then we started working at a local kennel as helpers." At the kennel, the Berg sisters learned about sledding. In just a couple of years, they went from one dog to four. Their team grew over the next few years to 14 dogs.

Sharing her idea of what it is like behind a team of eager Siberians, Berg says, "It really gets your heart racing when the dogs start running, and as you go around corners and down hills." Not satisfied with that, she adds, "It feels like you're part of the dog. And yet, you're part of the team." Pausing, she admits, "It's definitely something, but it's kind of hard to describe."

Berg urges people with Siberian Huskies, Alaskan Malamutes, Samoyeds, or other breeds, to give sledding a try. "It's great when I hook up six-month-old puppies and they want to run, like they've always done this. It's just in them, and it's neat to watch."

Johnson says sledding can reveal a dog's hidden personality. "I have a really shy dog," she says. "She wouldn't let anyone get close or pet her. But you put the harness on, and it's amazing. She becomes a different dog."

Getting Involved

Karen Ramstead remembers the day she bought her first Siberian Husky. "While I was there, they gave me a sled ride. It was the aha moment of my life. When I stepped onto that sled, I knew I found something big." Although she has followed her passion all the way to the Iditarod, she says, "The bulk of this sport is in recreational mushing."

To enjoy sledding, you do not have to live in arctic climates. You do not even need a sled. You can get similar experiences roller blading with your dogs, or having them pull wheeled vehicles on dry ground. "You still witness the same instincts," Ramstead says. "Even if you never race, you can still feel the excitement of being out there with your dogs."

In the early stages, people are often a bit over-eager. It is important to go slowly. If you have two or more dogs, they need to come together and get along as partners. You need to find that proper balance of being a commander while giving the dogs that measure of independence which is crucial for success and enjoyment. Mr. Finner cautions against thinking that you can just hitch up a team of dogs and take off through the snow. "If you go too quickly, it can be frustrating for you, and it can scare the dogs." Speaking from experience, he adds, "When we were first learning, we had a couple of situations where the dogs got all tangled up in the lines."

To avoid this, Berg says, "In the first year, just do very short runs, just to get out there and have fun. Develop trust with your dogs so they know you and you understand what they are doing."

Ms. Finner says to make contact with experienced mushers, then "Go out and simply watch them. You might think you're doing something wrong because your dogs aren't listening to you. Then you see experts run their dogs the same way, and you think, 'Wow, I'm not doing anything wrong—it's just that they are dogs!'"

There are many resources for people interested in sledding, including informational Web sites and a network of mushers throughout the country who are happy to show you their team, give you a ride on their sleds, and perhaps let you hold a puppy in your arms. Just watch out for Iditarod fever!