Musher Medicine: Sled Dogs Lead the Way to Health

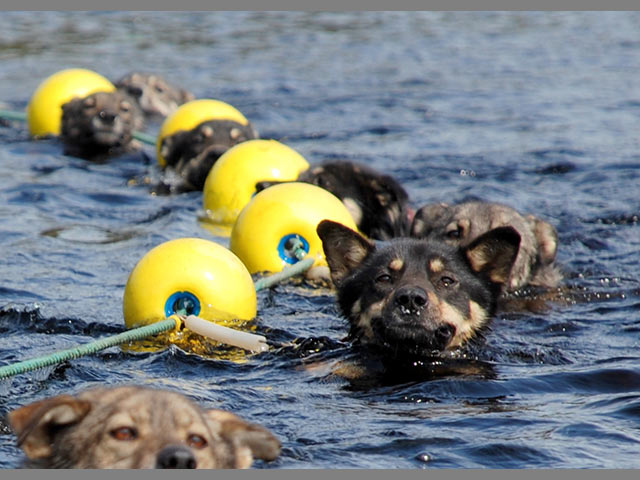

The desperate situation caught the attention of Alaskan dog sledders. Within days, sledders organized 20 dog-sled teams, 200 dogs in all, and made plans to carry the serum over 700 miles, forging through -62-degree temperatures, three-foot-high snow drifts, and life-threatening blizzards. Each sledding team would carry the serum part of the way, meeting at a designated check point to hand it off to the next team.

On February 2, Gunaar Kaasen rescued Nome, delivering 300,000 units of serum.

This story became known as "The Great Serum Run." It is legendary in Alaska. It also captured the imagination of Americans in the lower 48 states. In 1973, commemorating the The Great Serum Run, an annual race, the Iditarod, was established. At 1,100 miles and up to 20 days long, the Iditarod includes some trails covered by the original 1925 sledders (known as mushers).

Sledding Evolves

Much has changed since 1925. In that original, life-saving race, sleds were made of wood, with steel runners. The dogs ran "barefoot." Today, sleds are constructed of super-lightweight metals, with low-friction polymer runners. Sled dogs wear "booties" to protect their feet from freezing. Temperatures still plunge to -40 degrees, and the dogs often race through blizzard-like condition.

In the Great Serum Run, and in the early Iditarod races, dogs were harnessed up fairly quickly, and off they went into the wild. Today, each dog receives thorough health checks in the months leading up to the race. Veterinarians are on hand during the race for any medical needs. Before the race starts, all dogs are screened with an ECG to check their hearts, and a complete chemistry panel is done to confirm that that they are fit.

Researchers Discover Sledding

Just as the story of the Great Serum Run captured the popular imagination, the Iditarod caught the attention of scientists. What is it, some scientists wonder, that gives sled dogs the stamina to race with high energy and enthusiasm for 1,100 miles, in such harsh conditions? An increasing number of researchers have begun to travel to Alaska, to see what they can learn from sled dogs -- to improve sledding, and to provide insights into all dogs, even those who do not race.

Stomach Problems: Common in All Dogs

Michael Davis, DVM, a researcher at Oklahoma State University, grew up in Texas, where he knew nothing about sledding. He was interested in cold-weather-induced asthma, a condition human and canine athletes share. Davis wanted to see if sled dogs suffer damage from asthma-like conditions. It did not take long to realize that asthma is not a concern of sled dogs. But by the end of that study, Davis had become curious about sledding. He asked mushers to name the most common ailment. The answer that invariably came back was gastrointestinal (GI) problems. Davis, like most veterinarians, had known for years that GI problems are one of the most prevalent issues in all dogs. Why, he wondered, did sled dogs have a higher-than-normal number of GI problems? Davis looked more closely at sled dogs. "It turned out that the problem was much worse than anyone originally thought," he explained. He had found his next, and biggest, research project.

Stuart Nelson, DVM, is the chief veterinarian for the Iditarod. His job is to understand the health of all racing dogs and encourage research of the most common problems. "Sled dogs suffer from a high number of gastric ulcers, which happens to also be true of human endurance athletes. We've been looking at the best preventive measures for getting rid of this problem."

Nelson and Davis have focused, for now, on using standard, non-prescription medications, the same ones people use for stomach problems. Their challenge is to find which work best, and what the correct dosage should be. As Nelson explains, "Many of these medicines require dogs to limit how much they eat, which conflicts with the need of these dogs to consume tremendous amounts of food every day."

In recent years, they have found a combination of medications that reduces the number of gastric ulcers. Davis says the most important finding in his gastric ulcer work is how exercise affects all dogs. "When we first did this, we thought the problem would only be serious for dogs running 10 days straight. But we found that ulcers occur in dogs that exercise hard for just a single day."

Explaining the relevance to all dogs, Nelson says, "When you get into performance, whether it's sledding, hunting, agility, or any intense physical activity, there will be a connection here."

Another finding with wider significance is that gastric ulcers, while serious, remain invisible. "The Iditarod racers show no outward signs of having ulcers," Davis explains. "Field-trial dogs, agility dogs, or dogs who spend a selected period of time exercising, who don't show any signs of ulcers, may also be suffering from this."

Davis would like veterinarians to test working dogs more regularly for ulcers, which involves looking into a dog's esophagus with a special scope. "Working dogs are really tough," he says. "They won't show signs of illness or weakness, because they want to keep working."

Nelson is happy that the prevalence of gastric ulcers has been reduced. But he wants to do more. He and others will have to look beyond medications and figure out basic biological causes. "We think antioxidants might have a lot of benefit against ulcers," he reports. "If we could figure this out, we'd see wide-ranging application far beyond sledding."

Sled Dogs Help Improve What All Dogs Eat

One of the most immediate ways that sledding has provided knowledge benefiting all dogs is in nutrition. It seems natural that pet-food companies would be interested in looking at Iditarod dogs to test which nutrients provide the best fuel in extreme racing conditions. Albert Townshend, DVM, ran a successful veterinary practice in Maryland for 33 years. In 1991, he volunteered as a field veterinarian for the Iditarod. He was so impressed by the dogs' stamina and the dedication of the mushers that he decided to devote his energy to understanding canine nutrition through sledding. He sold his veterinary practice and became a staff veterinarian for Eagle Pack Pet Food, which develops dog foods for high-energy sports.

What Townshend and Eagle Pack sought to understand was, "How do you get enough food into a dog's stomach to provide energy for racing all day at top speed? These dogs consume about 12,000 calories a day during races. The diet needed to be energy-dense, but also highly digestible." He had to account not only for the dietary needs, but also the GI problems.

For 20 years, Eagle Pack has provided food for several Iditarod teams, analyzing their findings and tweaking ingredients to get the right formula. Townshend says the company's discoveries are relevant to all dogs who exert themselves, including ones who do rescue work, herding, police work, and hunting, as well as those who compete in agility and rally.

High-Altitude Discoveries

Jeff King has won the Iditarod four times. He moved to Alaska at the age of 19, and is now a full-time Iditarod trainer. Straddling the line between musher and researcher, King developed an elaborate facility to study his team as they prepare for the race. "At some point, I started thinking, 'we don't know the whole story. I want to go deeper, I want to understand and tweak each little factor.' I pick a specific area – nutrition, equipment, training schedules, calorie absorption." He has looked at genetics briefly, but, as he puts it, "I trust Mother Nature to have figured that out."

On those nights when King's dogs showed signs of fatigue from practice, he had an unscientific therapy. "I'm the first musher to have an indoor Jacuzzi for my dogs. It helps me when I'm sore, so I figured it would help the dogs."

The subject of fatigue soon became King's main focus as he took his inquiries far beyond the hot tub. In a building, which he calls "the barn," King created a system that mimics atmospheric conditions of 9,000-foot elevations. With a large mural of Mt. McKinley on the wall, he and his dogs sleep in the high-altitude chamber. "For two months, we set up controls. One group slept in the chamber, the other was out. We monitored the dogs' physiology."

King had a hunch that high altitude is beneficial, but even he was surprised at the results. "We took blood samples in a controlled program of exercise. We looked at red blood cell count and lactic acid. Not only did the dogs who rested at high-altitude have dramatically less lactic acid, but what they produced was flushed out of their systems way quicker than ones who weren't. They also had way higher red blood counts." Lactic acid builds up in the muscles of dogs and humans during exertion, creating fatigue. Red blood cells are responsible for carrying oxygen through our bodies.

The dogs do not train in the barn, King explains. They only rest there. "That calibrates the brain, trains it to recognize available oxygen levels, which tunes the whole body to utilize oxygen more efficiently." King says his dogs compete far better now, with less stiffness and soreness.

King understands that most people cannot put their dogs in high-altitude rooms. But what is relevant, he says, is that reducing lactic acid and increasing red blood count means dogs can perform better and more comfortably in any high-energy situation.

Future Promise

Emboldened by success, researchers want to look more closely at other health issues in the near future, focusing on Iditarod racers as a way to better understand all dogs.

Immune-System Paradox

Although the reasons are still unknown, sled dogs have a worse-than-average immune system. Davis believes a lot can be gained by studying this. "Sled dogs have under-built immune system, with fewer antibodies, and yet they don't have the infectious diseases you'd expect. Either what they have is incredibly efficient, or the way we measure immune systems is wrong." He intends to find the answer, perhaps gaining a better general understanding of canine infectious diseases.

Townshend sees the immune system paradox as a challenge for pet-food companies. It has long been theorized that beneficial bacteria in a dog's stomach aid the immune system. Eagle pack, and other companies, developed a line of foods known as "probiotics," which contain these beneficial bacteria. "The goal is to make it so each time the dogs eat they get inoculated with friendly bacteria," Townshend explains. "This should optimize their immune systems and help them digest better."

It is still an open question how sled dogs function better on weaker immune systems, and whether probiotics have long-term benefits. Putting together findings of researchers like Dr. Davis, along with pet-food companies' efforts, there is hope that sledders will provide answers.

Calling all Canine Couch Potatoes

Davis has recently been investigating basic metabolism, and how the canine body burns fat. When he looked at sled dogs, he saw some curious details. "We already know sled dogs burn an enormous amount of fat. But the way their cells efficiently burn fat is very unique. If we can figure out how these dogs throw the fat-burning switch, we could better understand obesity. Because sled dogs are so extreme, they are great to look at. This same thing is probably going on in other dogs, but it's too subtle. With sled dogs, it really stands out."

Davis observes that retired sled dogs, long after they have stopped racing, remain in excellent shape. "They are in the same kennels, eating the same foods. But they don't become obese. Why is that? Are they inherently resistant to obesity?" He wants to design a study that compares sled dogs with each other, and to other dogs, to figure this out.

High-Tech Ice Dreams

Nelson has immediate plans for improving the way we understand the health of sled dogs. "We're currently developing a system to save that ECG and chemistry panel data to create an ongoing record of all the dogs. We'll be able to go back through the years and do retrospective comparisons on the dogs' conditions."

Davis also says that improved technology can enhance research. "We're looking at ways to modify existing cardiac machines, so they can operate in extremely low temperatures without breaking. We just installed a large treadmill in Alaska where we run and monitor 16 dogs at once. This was a modification of treadmills built for US Olympic teams."

Nelson has even bigger hopes for human ingenuity. "I foresee a day when sleds have an instrument panel. All the dogs would be monitored and mushers could see the data as they race." This valuable real-time information could be collected and analyzed to better understand what allows these dogs to thrive in such extreme conditions, revealing some basic biology that would be useful in understanding all dogs. To make it happen, Nelson invites more researchers to take a closer look at the wealth of information available through the Iditarod. "Anyone out there who wants to do more, please contact me. I'm open, and I'm more than happy to speak with them."