Owner to Breeder, Part 2

These are not wolves. They are known as dog breeders. Each year, an increasing number of dog lovers choose to make the transition from dog owner to dog breeder. It is helpful for them to understand the social order they are about to enter.

Developing a Reputation

Leslie Ann Engen, who has bred Shiba Inus for 20 years, is blunt: "If you're a breeder, you don't just want to slap two dogs together. It's your responsibility to really learn the breed and produce puppies that represent the very best qualities. You have to start from square one doing the right thing."

A responsible attitude is important both to advance as a breeder, and as part of any effort to connect with the breeding community. These are like the Ying and Yang of breeding: you cannot succeed unless you gain the support of the community, and you cannot gain support without sending out informed signals about your goals.

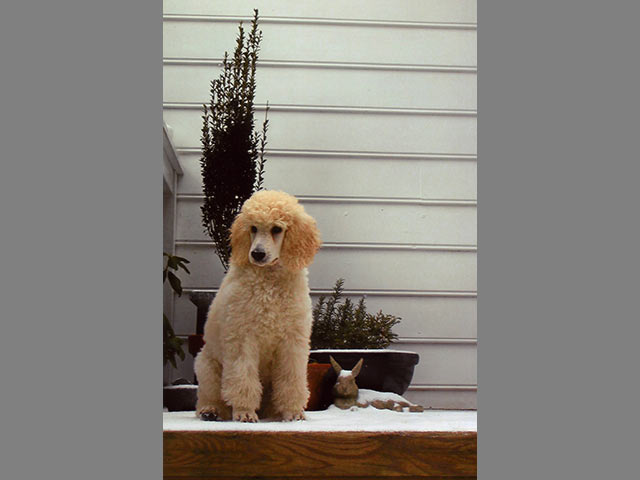

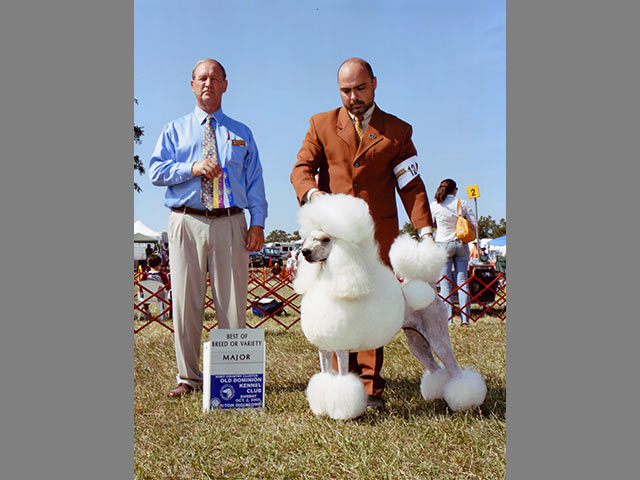

One of the best ways to show that you are responsible and serious is to wait until you have a female with numerous positive traits. This may sound vague, but most people who choose to become breeders do recognize whether their current dog is worthy of breeding. Bring that female to dog shows, show her to potential stud owners. Be prepared to describe her, let people meet her and check her history. "Don't start with a female that you will have to upgrade later," Ms. Engen advises. "Most breeders aren't going to spend their time working with you if this is the dog you want to breed. It's better to spay that dog and keep her as a pet. Then look for another dog that is a good representative."

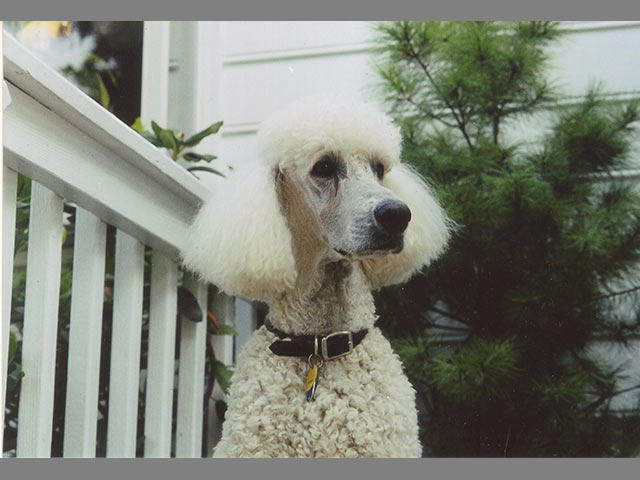

Sometimes, it is difficult for people to be subjective about their own dogs, a condition referred to as "kennel blindness." It can lead to errors in judgment, or unjustifiably lofty claims, which make a bad impression on experienced breeders – the very people you are appealing to for stud arrangements. Maggie Bryson has been involved with Standard Poodles since 1971, first as a breeder and now for breeder referrals. "Many times, people come in with their only dog. They love that dog, so they decide to breed her. But it's really a mediocre dog. Other breeders will see this. Right away, they'll think, 'Oh, this person is trying to start a puppy mill.' Then no one will allow you to breed to their dogs."

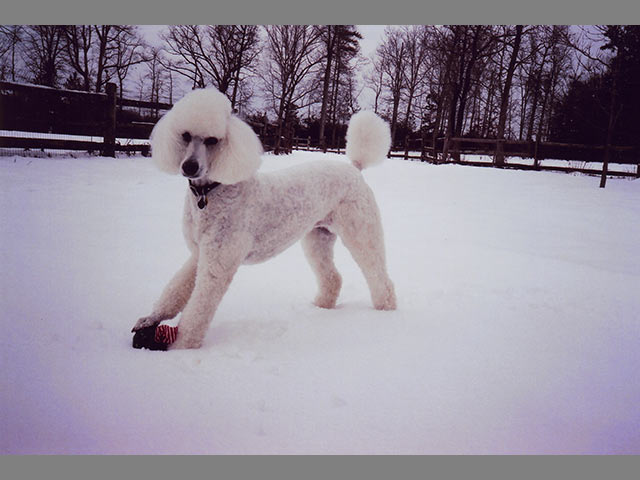

Another problem, Ms. Bryson emphasizes, is novices announcing big ideas that reveal a dangerous naivete. "For example, people want to emphasize a certain color. In Poodles, some people want to breed a beautiful, dark red color. But the trouble with this is, people who emphasize color too much are usually not paying enough attention to health and temperament. If all you're looking at is color, people see this, and it really bites you." A novice, stricken with kennel blindness, can quickly go from a nobody to someone who is known, but for the wrong reasons.

This all sounds harsh. But reputable, experienced breeders are selective with their stud dogs. If you shop around with a female you know is not the best candidate, it creates a negative image that persists even after you have found a better dog. With effort, you may correct this, but it is better to be prepared, and honest about your dog, before you seek to begin breeding.

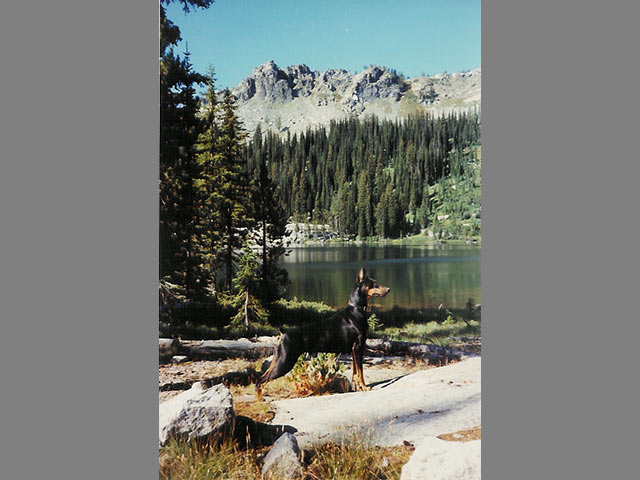

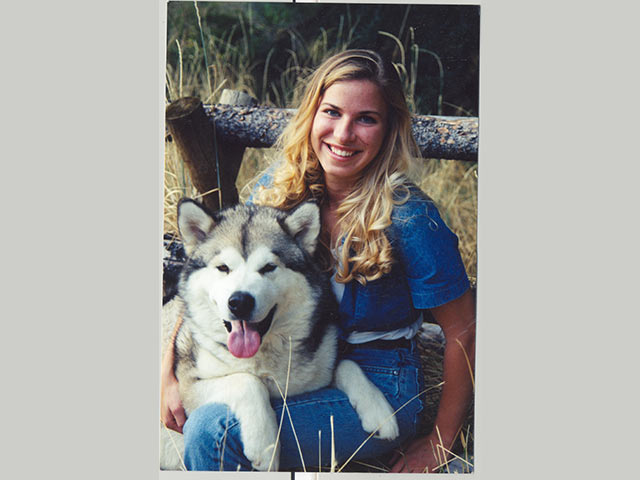

If you feel you have a perfect female, and you are ready to go forward, take your confidence, along with your dog, into the messy social world of dog shows. Leneia Rogowski has been breeding Alaskan Malamutes and American Eskimo Dogs for 15 years. She owned dogs for about three years before breeding her first litter. During those early years, Ms. Rogowski became confident that she knew what a great Malamute looks like, and was sure she owned one. She knew she had to grovel to make the right impression. "Remember, no one has to breed their dogs to you. When I wanted to make connections, I introduced myself at shows, gave people my background, told them they could check into anything they like. They could call my vet, and I gave them references – people I know who they might know."

Dealing with Criticism

Anyone who has spent time listening at ringside knows that breeders have sharp tongues. They are ready to pounce on anyone they think is breeding badly. Such criticism is not reserved for novices. The social scene at dog shows can seem rife with personal enmity, acid opinions, and sharp comments about almost any dog.

It is inevitable: if you become a breeder, no matter how well prepared, some ringside criticism will fly in your direction. With over 45 years of breeding experience, Mary Rogers has learned to trust her instincts, with dogs and people. She says you must expect criticism, about your dogs and yourself. "If you're sensitive to criticism," she says with a dry laugh, "you probably do not want to become a breeder." She says this, while admitting how difficult it was for her at first. "It used to be, if anyone said tough things about my dogs, I'd be crushed. I finally realized that it doesn't matter, unless it was coming from someone I respect, someone I admire for what they have accomplished."

In Ms. Rogers' view, the most successful breeders expose themselves to criticism, rather than shield themselves from it. "You need to show your dog to someone you respect, and ask, 'What do you think of her? Do you think she moves well?' Learn from that. The trick is to figure out who's worth listening to. You can usually tell by seeing who has had true success. Steer away from people who just go off on all the judges or are negative about other breeders. Over time, you develop a good sense of when to listen and when to push it away."

Mentors: Finding Calm Outside the Storm

Experienced breeders joke about unpredictable, shifting opinions and commentary in the show world. This may seem funny to those with years of breeding behind them, but it is maddening for someone just starting out. It is one of the main reasons people get burned out on the fancy. As Ms. Engen explains, "Most people only last four or five years. They get bored or frustrated, and move on."

While trying to find answers in the crowd, a novice should seek out a single person with knowledge and breeding success who can serve as a mentor, a guide through the breeding process, a liaison to the social scene. Ms. Engen holds mentoring as one of her central goals. "A good mentor will stimulate someone, get you to be an advocate for the breed. That inspires you, in turn, to share your knowledge with others. This is helpful, whether you want to show your dogs, do therapy, or simply produces good pets."

Connecting with a mentor has beneficial ripple effects for a new breeder, sending out signals to the community that you are serious, understand your responsibilities, are open to suggestions, and deserve respect.

Finding a mentor can itself seem daunting. Ms. Engen, who has served as a mentor for several new breeders, suggests going back into the show scene, but with a simple purpose. "You can find someone by word of mouth. Spend time asking around who is open to working with new breeders. You'll find someone who will help you."

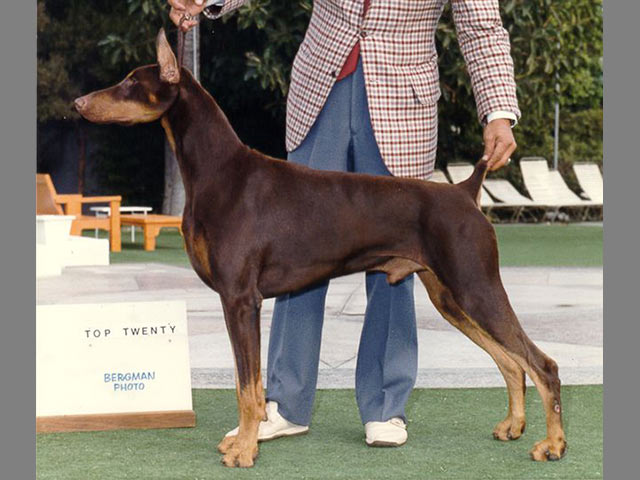

A mentor should be a long-term connection, not just a guide through your first or second breeding. Dani Edgerton has been breeding Greyhounds for 35 years, including more than 60 champions. She continues to rely on mentors. "I've become their equals, but I still need them," she explains. "I'll bounce ideas off them if I'm planning a breeding and there are health questions. I'll get their feedback on whether it's a good idea. If you develop this relationship, that person is always there for you. I would never breed without connections to people I trust to be honest with me."

Ms. Engen says that even if you have made mistakes, you can still find a mentor. "None of us was born knowing how to breed – we all had to acquire information about it. Sometimes, I meet people who had a bad breeding. But they come to me and say they're looking to make a correction. Part of the responsibility of any breeder is to help people you deem worthy of your time. It can be someone on any level, as long as they show a desire to help the breed you love."

Ms. Edgerton agrees, adding, "If you go to a fellow breeder and fess up that you made a mistake, you can ask that person how to fix it going forward. They can help you make decisions about what direction to head next." Doing this, she says, can be a great way to bring an experienced, and potentially influential person, into your long-term breeding goals.

Being "Clubby"

People either love or hate breed clubs. Whatever your attitude, there is no getting around clubs as central connecting stations in the society of breeders. Although Ms. Rogers was chosen as AKC's 2003 Breeder of the Year, she is a quiet person, describing herself as "not very clubby." Still, she has always been a breed club member. "Yes, club people often don't get along, and they do pile a lot of work on one or two members. But there are also great people in clubs, and you can learn a lot."

Ms. Rogowski has been involved in the Alaskan Malamute and American Eskimo Dog national breed clubs. "A lot of people worry that you'll have to change yourself once you join a club," she explains. "But you can just receive the newsletters and sign up for mailing lists. I know people who have been in a club for 25 years, but you'd never know it because they just sit in the back quietly."

Being in a club may help send out signals that you are serious, even if you have a relatively low activity level. It is also a great way to find a mentor.

If you have computer skills, communication talents, or leadership abilities, you might be "hired" for club jobs. Ms. Rogowski knows this all too well. "People found out I'm a decent writer, so I ended up doing the newsletters for the Malamute Club. Then the corresponding secretary resigned, so I 'filled in' for six months. Then I became the vice president of the American Eskimo Club" She has been in these jobs for several years.

Ultimate Goal of a Breeder?

In the end, it is back to the basic question: why be a breeder, and are you prepared to deal with the often incomprehensible social atmosphere of breeding and showing? Ms. Engen says the highest achievement is for a breeder to help other people who are thinking about breeding. "You must become a responsible breeder," she stresses. "That means you are instantly in the position of educating people about health and temperament. It's your job. This effort has tentacles that reach into the social world of breeding." The better you are at both breeding, and communicating your goals, the more satisfied you will be.

Ms. Bryson says breeders must have excitement that persists through the years. "I still love going to shows, watching dogs compete in agility and obedience. I study which lines perform well, which ones are stable and bright. Each year, I go to specialties. I'll be there for three days with my notebook writing down everything about conformation, health, temperament. That way, I have an idea what to say when novices come to me and explain that they want to breed their dog!"